AM Explainer: A Plain-Language Overview of Additive Manufacturing Technologies

By AMGTA

This is a reference article intended to support future analysis

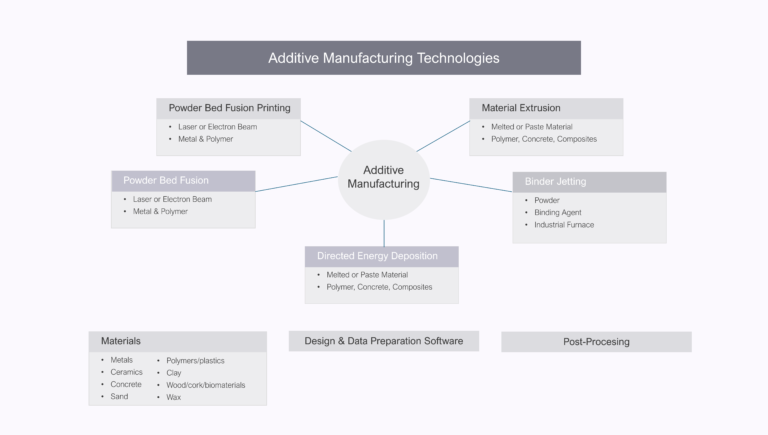

Additive manufacturing refers to a wide array of technologies centered on 3D printing, not a single technology or methods. The defining characteristic is a layer-by-layer approach to build parts from digital data, rather than subtractive manufacturing where material is cut away to form parts.

This layer-by-layer approach enables unique geometries, shapes, and pathways which are difficult if not impossible through traditional methods. While additive manufacturing introduces new manufacturing capabilities there are also distinct constraints. Understanding additive manufacturing begins with understanding how layers are created and bonded without focusing on individual machines or brands.

This overview is intended to be a high-level technical orientation without being a process manual, or selection or implementation guide. This guide operates at technical-method level and not at the qualification, certification, or application-specific performance level, which are addressed elsewhere.

Additive vs Subtractive Manufacturing

Traditional manufacturing methods typically form parts by removing or cutting away material (subtractive), forming shapes in molds, or deforming materials into specific shapes. Additive manufacturing works differently by adding material (additive) layer by layer, directly from digital data.

This structural difference – adding material rather than removing it – underlies the distinctive capabilities and constraints of additive manufacturing. This also explains why geometry, internal structures, and resource commitment impact manufacturing process differently than traditional methods. Additive manufacturing often requires little or no tooling (molds, jigs, fixtures) which can yield significantly reduced time lines and costs.

Design & Data Preparation Software

Additive Manufacturing relies on specialized design and data preparation software that translates digital concepts into manufacturable data. In many cases, this software enables, shapes, internal structures and voids, and material distributions that cannot be designed or interpreted using traditional manufacturing assumptions and limitations. The design processes for additive manufacturing often address part orientation, support strategy, internal features, and process-specific capabilities and constraints before the design ever reaches the 3D printer. While design and data preparation software do not fabricate parts directly, they are integral to how additive manufacturing functions in practice.

The design software enables design engineers to explore geometries not possible through traditional means. The layers that are produced on the 3D printer start as “slices” in the software – conceptually like the slices in a medical MRI.

Powder Bed Fusion: Fusing Powder with Energy

One of the most widely used additive manufacturing approaches is powder bed fusion.

In this method, a thin layer of powder – metal or polymer – is spread across a build surface. A focused energy source, such as a laser, is used to selectively fuse precise areas based on the digital design. Then another layer of powder and selective fusing. Layers of powder are measured in microns – approximately comparable to a single human hair. Over time a three-dimensional part is formed within the powder bed.

Unfused powder surrounding the part provides support during the build process enabling complex internal geometries and overhangs without additional tooling. Once the part is complete, unfused powder is swept away and recovered.

Powder bed fusion is commonly selected when organizations need:

- Complex geometry (including internal features)

- Repeatable, tightly controlled processing

- Material properties required for demanding applications

Powder bed fusion is also constrained by:

- Enclosed build chamber size

- Requirements for controlled build conditions – often requiring inert gases

- Post-processing to remove powder and achieve final surface and fit requirements

Material Extrusion: Depositing Material Layer by Layer

Another often-selected category of additive manufacturing is material extrusion.

In extrusion-based systems, material is pushed through a nozzle and deposited in layers. The materials can be melted, softened, or in a paste or solution form, depending on the application.

For polymers, this process often involves heating solid material in a filament, pellet, or powder form so that it can be deposited based on the digital design. In other contexts, extrusion systems deposit materials such as composites, pastes, or construction-grade compounds that harden as they cool or dry.

Material extrusion system vary widely in size from enclosed desktop printers to robotic arms printing houses.

Tradeoffs typically include:

- Lower resolution compared to powder bed fusion

- Greater dependence on material behavior during deposition

- Need for support strategies depending on the design

Directed Energy Deposition and Hybrid Systems

Some additive manufacturing methods deliver material, often metal wire or powder, directly into a focused energy source. These approaches are often used for larger components, component repairs, or hybrid manufacturing environments combining both additive and subtractive processes.

Binder Jetting: Shaping First, Strengthening Later

Binder jetting takes a different approach and possibly most deserving of the “printing” moniker.

In this method, material powder is spread and a binding agent is deposited based on the digital design rather than fusing material with a laser. The binding agent is applied through a print head very similar to the print head in an ink-jet document printer. The resulting part is often referred to as a “green” part, that has shape but not strength.

After printing, the part undergoes further processing such as sintering – often in an industrial furnace – to achieve the desired material properties through heat and time.

Binder jetting is often valued for:

- Efficient production of multiple parts in a single build

- Separation of shape creation from material densification

- Applicability to metals, ceramics, and other powders

Final properties depend heavily on post-processing, finish machining, and process control rather than the printing process alone.

Vat Polymerization (Resin-Based Methods)

Some additive manufacturing methods use light to selectively curing liquid resin to build parts in a tank. These methods are often used for high-resolution polymer parts and tooling.

While the materials and physics differ from powder-based and extrusion methods, the core principles are the same: solidifying materials layer by layer from digital data to create parts.

Cold Spray

Cold spray is a method for depositing materials that does not require meting or creating a extrudable paste or using a binding agent.

Cold spray uses high-velocity gas (like nitrogen or helium) accelerated at supersonic speeds to deposit metal powders on a substrate and deforming plastically to bond without melting.

Cold spray has many benefits:

- Solid-state bonding

- Retains material properties

- Repairs existing parts, large build sizes, faster deposition rates

- Create near-net shape rapidly

- More flexible in challenging, remote, and moveable environments

Some limitations exist:

- Not as precise as other methods

- Requires post-machining for fine tolerances

- Challenges with tall, thin features

Materials as Engineered Inputs

Across the various additive manufacturing methods, materials are not simply off-the-shelf.

Many additive processes require materials to be specifically designed and produced for that method. Metals, for example, are often converted to powders with strict particle size and shape requirements which impact flow rates and the quality of the part. Polymers may be formulated as filaments, powders, or liquids depending on the intended printing method. Polymers are also specifically formulated to deliver the necessary material properties in the resulting parts.

While polymers and metals are the most common additively printed materials, virtually any material which can be melted or made into a paste-like consistency can be printed including: ceramics, concrete, sand, wax, and clay. Additionally, many bio-based waste/byproducts such as wood, cord and even fruit pits can be ground into powder and converted into a printable form.

These material forms are engineered inputs, not accidental choices. These materials influence process behavior, part quality, post-processing requirements, and qualification pathways.

Printing Is Only Part of the Process

Across nearly all additive manufacturing methods, the printed part is not the finished part.

Heat treatment, curing, sintering, surface finishing, machining, and inspection are often required to achieve necessary tolerances and surface finish. These processes cannot be overlooked in understanding additive manufacturing in practice. The need for post-processing or achieving near-net shape does not diminish the impact of additive manufacturing; it identifies the separation between building geometries and achieving performance.

Size, Scale, and Constraints

Additive manufacturing methods differ significantly in how size is constrained or not.

Some processes are limited by an enclosed build chamber. Others operate with minimal enclosure and produce very large parts or structures. Build environments effect not only the size of parts possible but also the impact on materials as they solidify. Additive manufacturing’s layer-by-layer approach not only enables intricate internal geometries but also enables part consolidation. Systems are usually segmented based on traditional manufacturing constraints. With regard to additive manufacturing, it is often said that complexity is free. Combining multiple components into a single part is no more complicated to produce than the individual components.

Boundary Conditions and Technical Rigor

For regulated or high-performance applications, additive manufacturing must meet qualification, certification, and standard requirements that vary by application and industry. Current standards are based on traditional manufacturing capabilities, constraints and accepted practices. These considerations are real and consequential.

This overview does not attempt to resolve those technical boundary conditions. It assumes that material performance, process control, qualification, and certification remain essential and are addressed through established technical pathways.

A Family of Methods, Not a Single Technology

The most important takeaway from this overview is that additive manufacturing is not one method, one material, or one scale.

It is a family of methods unified by a layer-by-layer, digitally designed and controlled approach to building parts and systems, but differentiated by how materials is delivered, bonded, and finished.

This technical diversity explains both the potential and complexity of additive manufacturing. This also helps explain why discussions of strategic impact must not get locked in technical feasibility and miss organizational interpretation, as outlined in the accompanying materials. (link to Technical Boundary Overview)